- About half of Batswana say they felt unsafe while walking in their neighbourhood (50%) and feared crime in their home (45%) at least once during the previous year. Urban residents and poor citizens are considerably more likely to be affected by such insecurity than their rural and better-off counterparts.

- About three in 10 citizens (29%) say they requested police assistance during the previous year. More (37%) encountered the police in other situations, such as at checkpoints, during identity checks or traffic stops, or during an investigation.

- More than one-third of citizens (36%) say that “most” or “all” police are corrupt – the fourth-worst rating among 11 institutions and leaders the survey asked about.

- Fewer than half (46%) of Batswana say they trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot.” Poor citizens are far less likely to trust the police (32%) than those who are economically better off (47%-56%). The share of citizens who say they don’t trust the police “at all” has almost doubled since 2019.

The 2016 World Internal Security & Police Index ranked the Botswana Police Service as Africa’s best (47th worldwide), highlighting low levels of corruption and strong public confidence in the police at the local level (International Police Science Association, 2016). Police officials cited community policing in partnership with local organisations and traditional leaders among their crime-fighting strategies (European Times, 2016).

More recently, however, Botswana’s police has made headlines for its use of force, including last year’s fatal shooting of nine suspects in a cash-in-transit robbery (Ndebele, 2022) and of two bystanders – along with three suspects – in response to another robbery (Mmegionline, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the police was repeatedly accused of brutalising citizens in the name of enforcing lockdown restrictions (Makwati, 2021). Members of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of Parliament have raised concerns about police brutality (Mmegionline, 2021), and President Mokgweetsi Masisi issued a statement condemning police violence and promising accountability (Pindula, 2020).

Critics charge that officers accused of abuse often go unpunished, and an effort to establish an Independent Police Complaints Commission have so far been fruitless (Law on Police Use of Force Worldwide, 2022).

This dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2023) questionnaire to explore Africans’ experiences and assessments of police professionalism.

In Botswana, citizens offer mixed assessments of police integrity, trustworthiness, and conduct. While relatively few report having to pay bribes to the police, most say at least some officers are corrupt, and fewer than half say they trust the police. Poor people are particularly likely to see the police as corrupt and untrustworthy.

Majorities think the police at least sometimes use excessive force with criminal suspects and engage in illegal activities themselves, and only a minority say the police generally operate in a professional manner and respect all citizens’ rights.

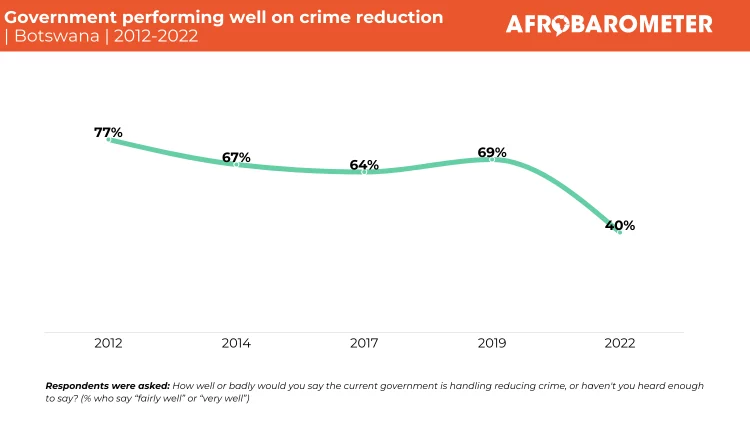

Overall, about half of citizens report feeling unsafe during the previous year, and approval of the government’s crime-reduction efforts has plummeted in the past three years.

Related content